Most World Cup Talent Are Born in France (Data Analysis)

We set out to find the city with the most football stardust in their water. The short answer, it's the one on the river Seine. However, we stumbled on some intruiging results on a national level as well. In the last two decades France have graced the football masses with more talent at the World Cup than any other country. We are not even counting the 1998 triumph on home soil.

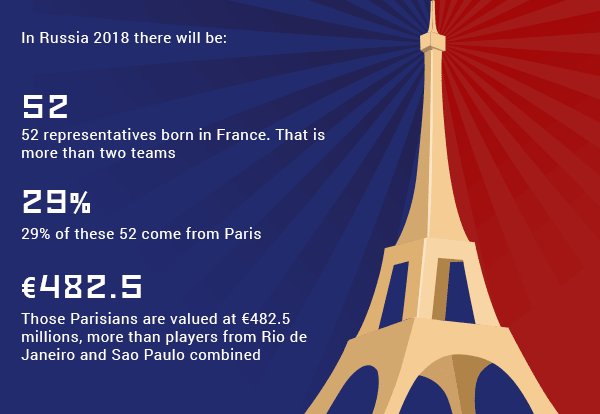

52 representatives at the 2018 FIFA World Cup were born in France

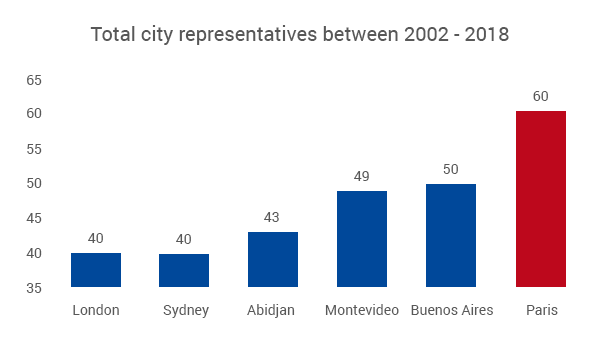

This French expansion can be traced back to Isle of France, or Ile-de-France, the administrative region for Metropolitan Paris. It is often referred to as ‘the city of love’ or ‘the city of lights’, now it can officially be called ‘Paris, the city of incredibly talented soccer players’. Just like the capital’s nation state, Paris has provided more personnel to the World Cups than any other city in the world.

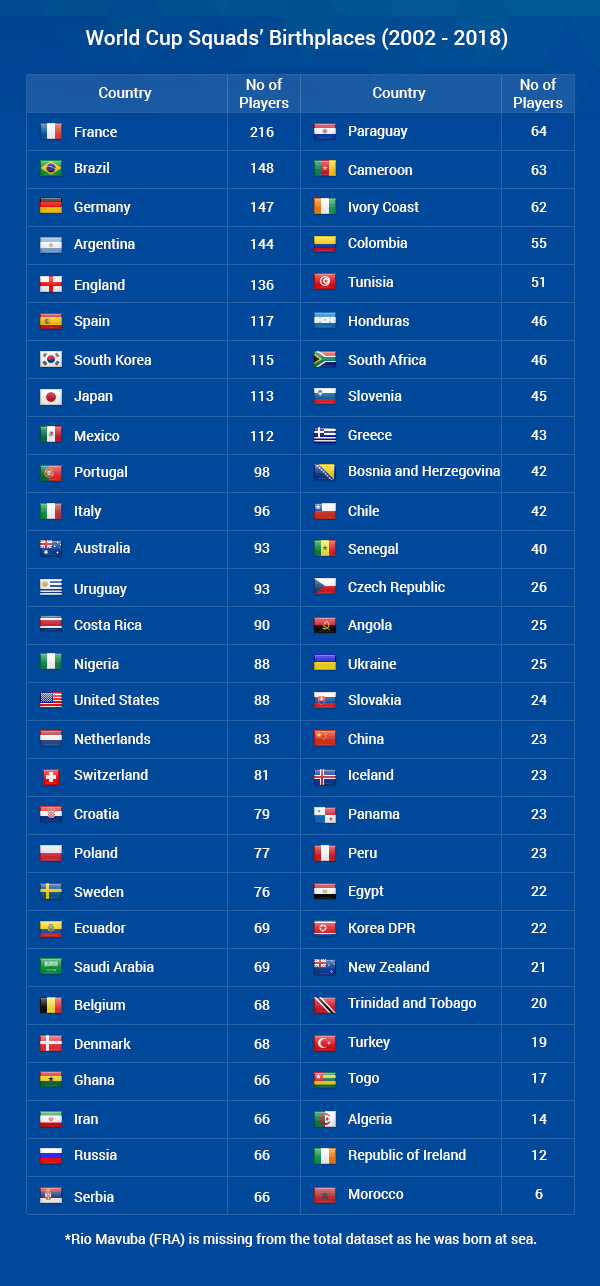

Our dataset consists of 23 players and one coach from 32 competing nations across five World Cups since the turn of the millenium. That is a grand total of 3,840 participants. We re-counted recurring player’s and coach's birthplaces as they had to earn their positions in the final World Cup squad each time. Here are the totals:

So, within the lifetime of a millenial, France have accrued some seriously impressive statistics over their World Cup counterparts. For example, this year in Russia, 52 players can claim to be born on French soil.

This is more than two full squads, or, just three players shy of fielding five starting line-ups. It’s worth repeating that again, most national football associations struggle to come up with one team that is good enough to take them to the World Cup, France however, have almost five.

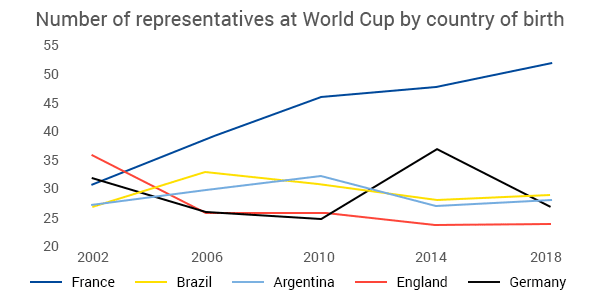

Remarkably, they have managed to up the ante with every subsequent edition since Japan and Korea in 2002. Appearances at the World Cups from French born players increased by 67.7%. In that time, they have amassed 216 names on the squad lists. That is 68 players more than the next most represented nation, Brazil, the ‘notorious’ footballer exporters.

France’s neighbours Spain are sixth on this list with 117 World Cup stars born within their shores. To the east of the border, Italy squeeze into the top-ten list with 98. That’s less than double the French quota. The dominance here is made more impressive when you subtract the 12 players that represented Les Blues in the last five World Cups who were born outside of its administrative land.

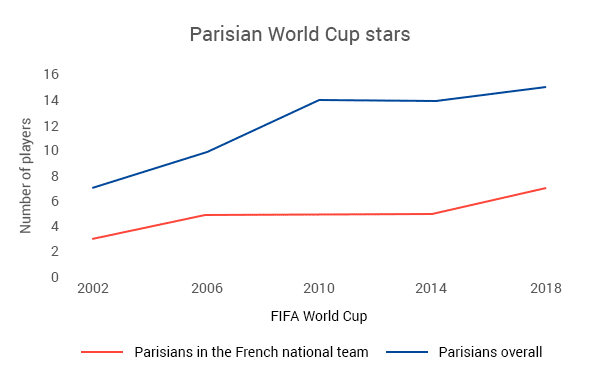

Yet, this overall French upsurge can be attributed to Paris and its banlieues who more than doubled their numbers in the same time frame. Their increase of player provision to the Copa Mundial is up by 114.3%.

Paris provides more World Cup players than any other city

By gifting us 60 talents at the grandest of stages, Paris is the clear answer to our initial research question. To put that into perspective, it is an average of a head-coach and a starting 11, all from the same city, for the past five World Cups.

I know what you’re thinking, 'how is this possible? Surely Buenos Aires or Sao Paulo provide the most football talent to the world’. Well, Sao Paulo* does not even make the top-six list with a meagre 27 representatives, while Buenos Aires give a good account of themselves here with 50.

Together with Brazil, none of the other football powerhouses such as Spain, Germany and the Netherlands have a representative city on our top-six list. They all seem to have a pool of talent sprinkled across the nation, a collection of big fish in various size ponds when compared to the gam of sharks in the Parisian Piscine Molitor.

*Sao Paulo including the ABC region. Read below for details.

Though, this was not always the case for France and Paris. As the chart below shows, there has been a steady rise in quantity over the past two decades. This suggests that in the previous French World Cup squads, the talented were more evenly spread across other parts of the nation.

When scaled to city / country population ratio, at the 2002 World Cup there were an under representation of Parisians in the French national team by 6%, but by 2018 they have amassed an over representation by around 10%. Within the French squad of 23 players (plus one), there is an increase of Parisians by a hefty 133%.

Honourable mentions to Abidjan, Montevideo and Sydney whose representative nations made it to three, four and four out of the five World Cups respectively. However, had those cities provided good enough players to attend the World Cups they missed out on, then we may have been writing about their cities. As it is, the best they can do is get a shared paragraph in an article about a city with the most World Cup talent.

The numbers certainly stack up for the Parisians here, but they do have a peculiar advantage over some of the aforementioned heavyweights, one we discuss later on in the article. However, they do not just make up the numbers either. In Russia, the talent on offer in a hypothetical all Parisian line-up is overwhelming to say the least.

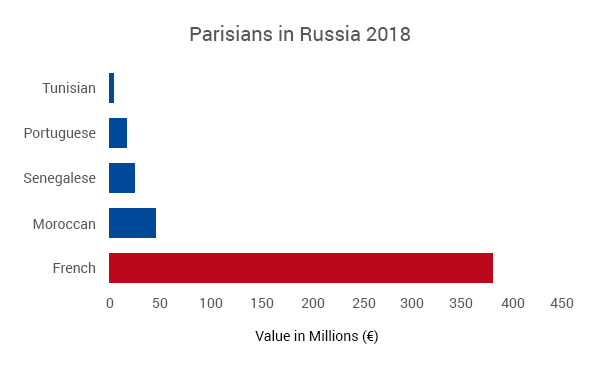

€482.5 million worth of Parisian talent in Russia

Safety in numbers is well and true but football is ([un]fortunately) a business and you would be forgiven for wondering whether these Parisians are worth anything. Well, just like most things in Paris, they don’t come cheap.

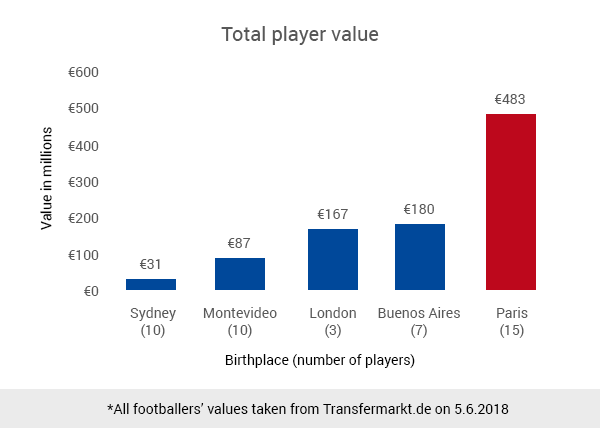

Of the top-six cities with the most players under consideration here, Abidjan does not come under our monetary scrutiny as Cote d’Ivoire missed out on the current World Cup. However, a notable exception is Rio de Janeiro who are bringing €221 million worth of ability to the big dance in Russia.

Yet, if we combine Rio de Janeiro’s total value with the total value from Sao Paulo* (€211 million), the samba boys still fall short of the lofty Parisians by €50.5 million, or roughly, the net worth of the entire Australian squad, with leftover change for a tip.

The chart above can be compared with the Burj Khalifa and the Dubai skyline in more ways than one. The Parisians in Russia are a total net worth of €482.5 million. It is not so difficult to understand why Oryx Qatar Sports Investment group have invested so heavily in Paris Saint Germain since their takeover of the club in 2011.

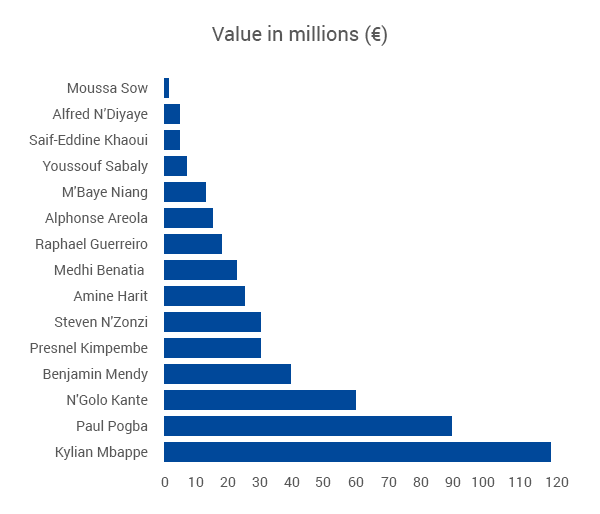

Merely two seasons ago, Paul Pogba shattered the world transfer record when he re-joined Manchester United for a mind-numbing €110 million. Now, the midfielder is not even the most expensive player to come from Paris.

That honour goes to the teenager Kylian Mbappe who is set to complete a €180 million transfer to hometown club, Paris Saint Germain. The two record-breakers combined are worth more than all the Buenos Aireans in Russia.

Of the top four Parisians at the 2018 World Cup in the chart above, Kylian Mbappe and Benjamin Mendy are still considered youngsters at 19 and 23 years old respectively. This means that the current valuations for the young pair are set to increase. While Paul Pogba, 25 and N’Golo Kante, 27 are on the cusp of entering prime age for central midfielders, they too, can expect their price tag to soar, especially if France have a good World Cup.

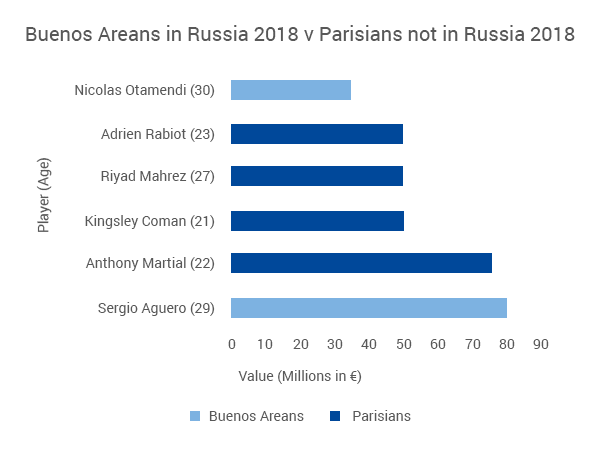

By way of comparison, Sergio Aguero (€80 million) and Nicolas Otamendi (€35 million) are the most expensive Buenos Aires products. Though, the Manchester City teammates are 29 and 30 years old respectively. Their valuations have surely reached the apex and can be expected to descend in the coming years.

For further proof of the riches to come out of Paris, if at all necessary, below is a chart depicting how the pair of Argentines stack up against Parisians that did not make it to this year’s World Cup. Notice that the average age of these unfortunate Parisians is only around 23. It says a lot about the strength in depth when you can afford to leave out a €75 million rated youngster from the final World Cup squad.

Laws of the game

The most difficult task of this investigation was defining the limits of a given city. Some modern megacities have swollen to such extents that they have absorbed everything in its purlieu – including other perfectly serviceable cities of their own merit – creating large urban conurbations.

For example, Incheon, a historic port city in South Korea, has an ample three million dwellers, yet it’s population count is merely added to the digits of the Seoul Capital Area’s metropolitan region, an agglomeration with a total population of 25 million.

However, if this study were solely focused on finding out where South Korea’s footballers were born, then we could have used metrics specific to South Korea, such as administrative or statistical areas. It becomes a lot trickier when comparing international cities as each country has varying methods of designating boundaries of cities and urban sprawls.

Our criterion of a city is that it needs to have a major economic and cultural centre with a surrounding (sub)urban area that is dependent on the economy of said centre. The boundary is where the (sub)urban area meets the rural area.

In the case of the Seoul Capital Area (where Incheon and Suwon contribute to the fifth largest metropolitan population in the world), we consider this conurbation as multiple separate cities and turn to the country’s administrative divisions to distinguish their borders.

Same principles are applied to San Jose, Alajuela and Cartago in Costa Rica; likewise, for Santo Andre, Sao Bernardo do Campo and Sao Caetano do Sul, commonly known as the ABC region in Sao Paulo, Brazil. These cities are all largely interdependent of each other despite being linked by a continuous urban sprawl.

Below is a heat map of all the birthplaces from our dataset.

Diversity makes Paris the winner

In order to preserve the integrity of the international competition, FIFA tightened the rules on nationality and representation in 2004. The decision arrived amid a growing trend of so called ‘lesser’ footballing nations naturalising players from a greater talent pool, typically from Brazil, to play for their national team.

For example, Qatar offered citizenship to three Brazilians within a week having never lived or played football in the country, while Togo managed to naturalise five Brazilians for their national team.

To prevent this, FIFA declared that any player wishing to represent a ‘new’ nation must have a ‘clear connection’ to it. A ‘clear connection’, according to FIFA, means that a player must have at least one parent or grandparent who were born in their newly chosen country.

The diversity of France, and Paris in particular, lends a hand to the range of national teams its citizens can represent. Along with many European migrants residing in Paris, France’s colonial history also means that a large proportion of African and Caribbean immigrants call Paris home.

Famed French nationals Claude Makalele and Lilian Thuram both migrated with their families to Paris from Zaire (modern day DR Congo) and Guadeloupe respectively. They belong to the minority of footballers to go in the opposite direction.

Though, Lilian Thuram was technically born a French citizen, Guadeloupe still have their own national football team that competes in CONCACAF competitions.

By law, the French INSEE census does not collect data on religion or ethnicity so it is difficult to estimate the extent of diversity in the Ile-de-France region, but approximately 20% of its inhabitants were born abroad.

One might conclude that an even larger percentage have at least one parent or grandparent who were part of the sizeable waves of immigrants arriving to Paris since WWII.

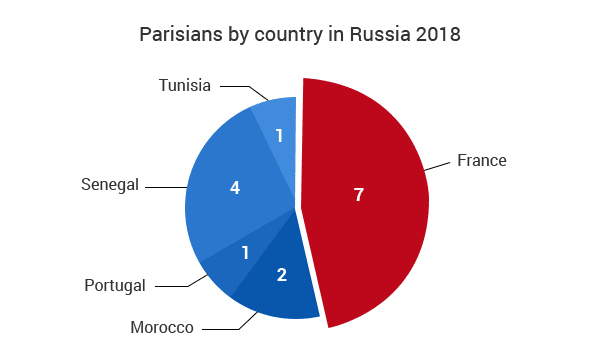

The advantage Paris has over Buenos Aires – its closest challenger in our study – is that a vast majority of professional footballers may feel that their best opportunity to play for a national team would be with the country of their heritage. The following chart indicates the gulf in value between the representatives of France versus other football associations.

Senegal’s Moussa Sow may not have had plenty of chances to play for the senior French national team, instead he has accumulated 50 caps across three Africa Cup of Nations and is set to play in his first World Cup.

Whereas Buenos Aires citizens are concerned, they are largely of European background and particularly from Italy, Spain or Germany. With no disrespect to African footballing nations, the European trident’s national teams are a lot tougher to break into.

Likewise, these waves of migrations chiefly occurred in the late 19th century and up until WWI. It is unlikely that the current crop of footballers would have many feelings of nationalism toward the faraway countries of their grandparents. Much of the same could be said for Montevideo.

Now, as is the norm with such analyses one needs to conclude with the answer to the ultimate question. Having so much talent within their ranks, will France be victorious in Russia 2018? On paper, they certainly should be, however, football is played on grass. At least they will always have this article for bragging rights.

About the author

Darko Dukic is fascinated by the good, the bad and the ugly sociological aspects of the beautiful game. Previously he taught Sociology of Sport at Victoria University, Melbourne and tried his hand at playing and coaching football. Please feel free to reach out to him with your football musings at darko@runrepeat.com.

About RunRepeat

RunRepeat is a team of shoe geeks who buy the shoes on their own, wear test all the shoes and them test them in the lab. This way, all the shoe reviews are as unbiased as it gets. We use durometers, calipers, a dremmel, a smoke machine, a force gauge, a band saw, and other instruments to deliver 20+ data parameters for each shoe. This way, we can rate the shoe's breathability, flexibility, softness, and durability. To learn more about our lab tests, see our Methodology page.