All Eco Sneakers Do Is Kill The Planet a Little Bit Slower [Study]

The threat from climate change is greater than ever.

Recently a number of sustainable sneakers have entered the market.

But does anyone actually know what environmental impact their sneakers have?

It turns out that if the sneaker industry was a country, it would be the 17th largest polluter each year.

That raises one question in particular: how much do these 'eco-sneakers' actually reduce carbon emissions by?

Well, not as much as you might hope.

Eco-sneakers are not going to save the planet.

In fact, all they’ll do is kill it a little more slowly than conventional sneakers.

The average eco-sneaker cuts emissions by less than 10%. Meanwhile, only 1 in every 29 pairs of sneakers on the market qualifies as an eco-sneakers.

Even worse: on average brands charge an additional $48.79 for a pair of eco sneakers -- essentially profiteering from consumers' desires to save the planet, or incentivizing consumers to buy conventional sneakers with even higher carbon emissions.

Environmental Impact of a Conventional Pair of Sneakers

Before getting into the weeds, it’s to understand how conventional sneakers are made and their environmental impact. This way, there is a baseline.

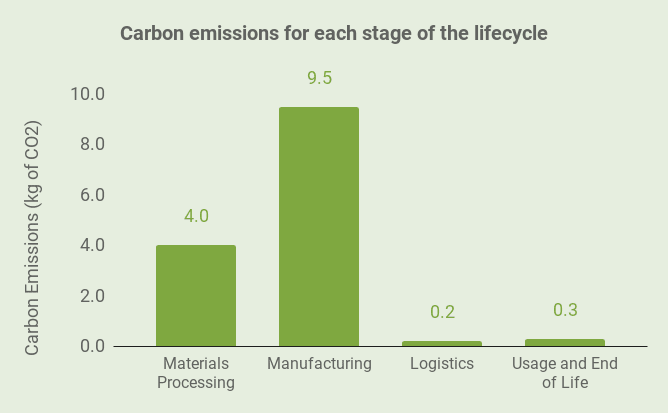

Carbon emissions over the life cycle of a pair of sneakers

| Carbon Emissions |

| 14.0 kg |

When a group of researchers at MIT performed a life-cycle assessment (LCA) of a standard pair of sneakers, they found a typical pair of running shoes generates 14 kg (30 lbs) of carbon emissions.

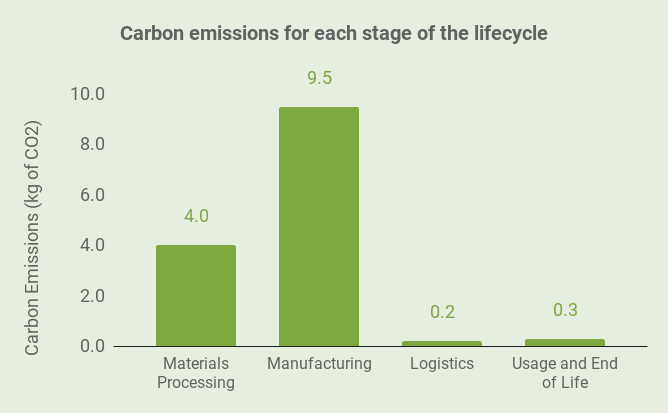

The stages of that lifecycle are:

Material Processing - Raw materials being farmed (natural materials) and materials being created (synthetics) to the point where they’re ready to be used in the manufacturing process. The main emissions from the energy associated with processing synthetic materials so they’re ready to be used in the manufacturing stage.

| Carbon Emissions |

| 4.0 kg |

Manufacturing - Taking the processed materials and turning them into the final product. Includes processes such as cutting and stitching the upper, pressing the midsole and outsole, and injection molding. The main emissions come from the energy used in factories (often in China or Vietnam) that produce the shoes.

| Carbon Emissions |

| 9.5 kg |

Logistics - Transporting raw materials to factories, transporting finished goods to markets where they are sold. Emissions come from fuel used to transport the finished product from the factories in Asia to western countries where they’re sold.

| Carbon Emissions |

| 0.2 kg |

Usage and End of Life - Includes any energy that is used during the life of the sneakers. The end of life includes disposal of the shoes and the impact that has on the environment. When in use, the only real emissions are when the sneakers are washed. At end of life, the majority of sneakers (more than 85%) are sent to landfill or incinerated -- releasing harmful chemicals.

| Carbon Emissions |

| 0.3 kg |

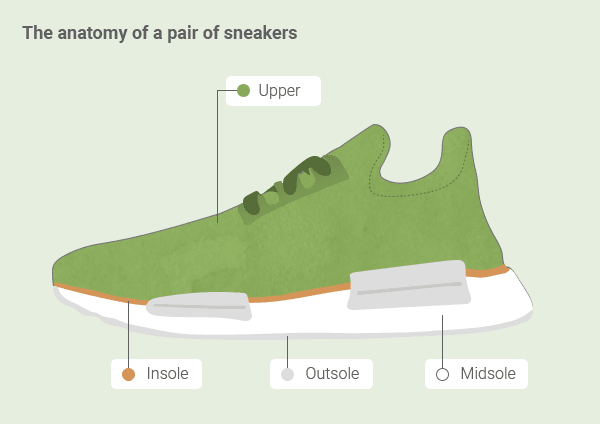

The anatomy of a pair of sneakers

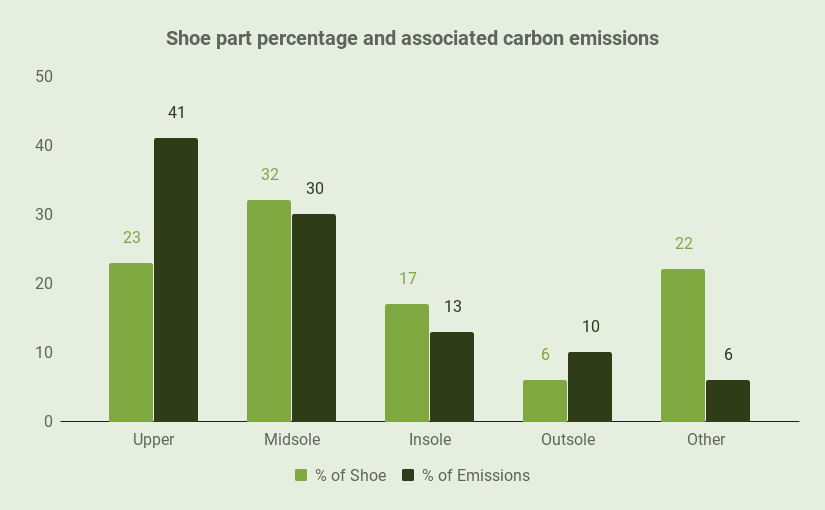

On average, sneakers have around 65 distinct parts. But, there are 4 or 5 major parts that make up every sneaker.

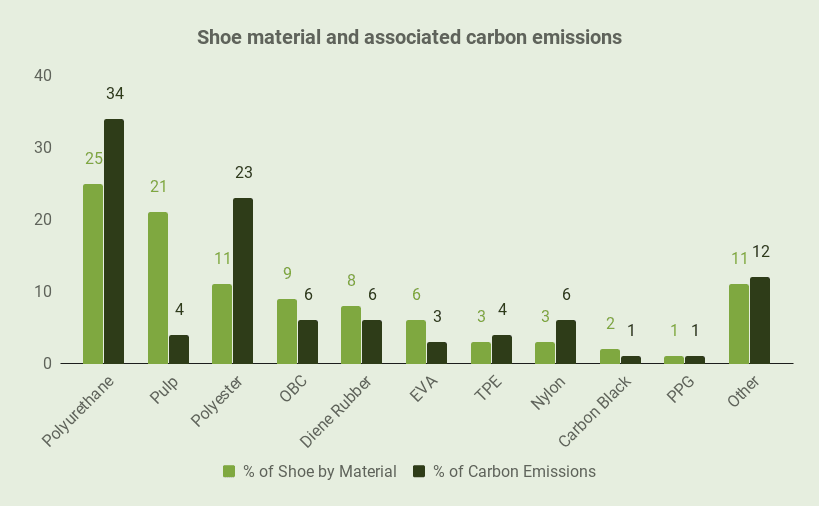

Materials in Sneakers

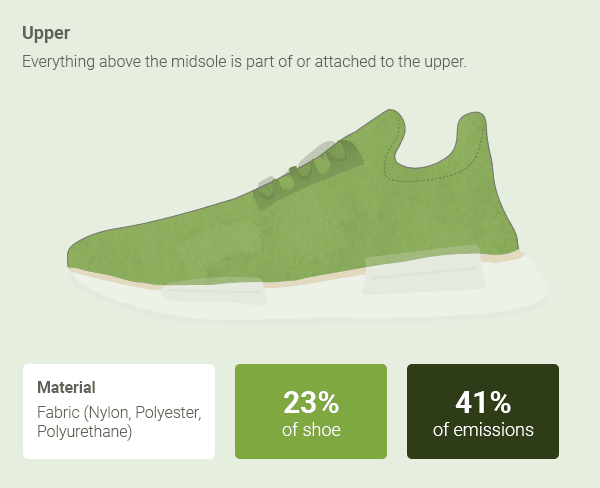

Polyurethane and Polyester are responsible for the majority of the carbon footprint. Nylon also has a disproportionate impact. They have such a large impact on the carbon footprint because of the amount of energy required to process the materials.

The green alternative is using recycled materials. Recycled polyester uses up to 84% less energy to produce than virgin polyester.

The upper is made up of Nylon, Polyester, and Polyurethane, so it’s responsible for the largest chunk of the carbon footprint.

Looking at the emissions associated with materials, it makes sense to source alternative, more eco-friendly materials for the upper and the midsole.

Summary of Environmental Impact

By looking at the carbon footprint, it is clear that the first two stages (materials processing and manufacturing) make up 92.8% of the carbon footprint.

By itself, the manufacturing stage contributes 64% of the carbon emissions.

Without updating manufacturing processes, major companies are not going to make meaningful strides in reducing carbon emissions -- regardless of what material the sneaker is made from.

Eco-Friendly Sneakers

From the MIT study, there is an established baseline of 14 kg of carbon emissions for the lifetime of a conventional pair of sneakers, and an understanding where the emissions come from.

From this, an analysis of eco-sneakers can take place to determine their credentials as sustainable products.

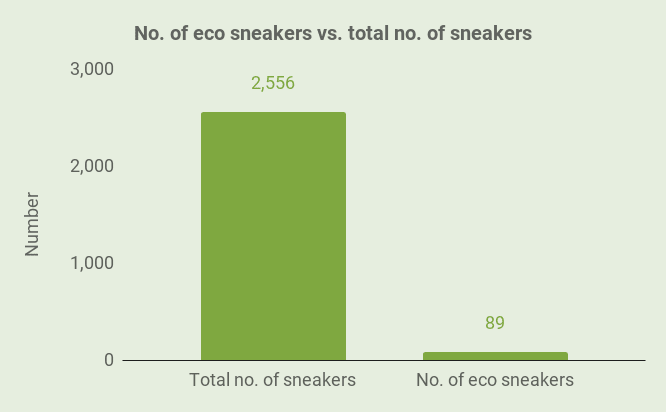

RunRepeat has one of the largest databases of sneakers around -- with 2,556 shoes from 34 brands. 89 of those are classified as ‘eco-friendly.’

That’s only 3.4%. Or, 1 of every 29 pairs of sneakers.

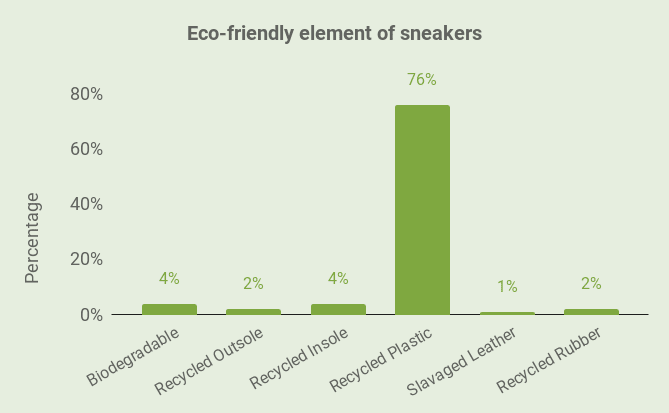

Of the 89 sneakers, more than 95% include recycled plastic.

For example, the Adidas NMD_CS1 Parley Primeknit. Up to 95% of the Primeknit in the shoe’s upper is made from plastic bags salvaged from the ocean in partnership with Parley for the Oceans.

The same story the Nike Free RN Flyknit MS. They incorporate Nike’s own polyester knit material into their design. It’s made from plastic bottles diverted from landfill and that are recycled into polyester thread.

Brooks manufacture running shoes with a biodegradable midsole to lessen the end of life impact of their shoes.

Let’s look at the numbers with some specific examples.

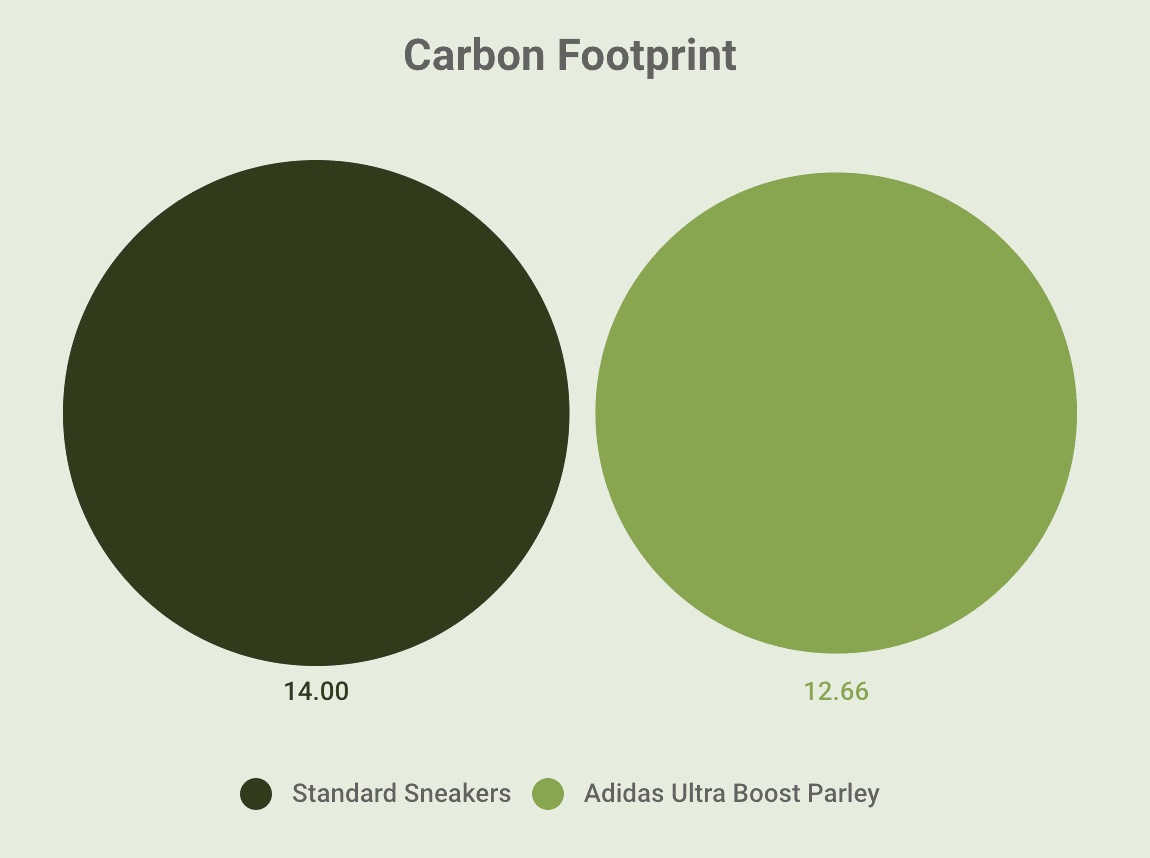

Adidas Ultra Boost Parley

| Carbon Emissions | Reduction in Emissions | % of Reduction |

| 12.66 kg | 1.34 kg | 9.6% |

The Adidas Ultra Boost Parley is made using plastic bottles (around 11 per shoe) retrieved from the ocean. These are turned into Primeknit material. Adidas claims 95% of the upper is made from recycled plastic bottles.

It is possible to calculate the carbon footprint of these sneakers by using knowledge gathered from the MIT study covering conventional sneakers.

The upper makes up 41% of emissions in the materials processing stage.

So, in a standard sneaker, 1.6 kg of the 4 kg of CO2 in the materials processing stage can be attributed to the upper.

By taking out the existing material in the upper completely, it would reduce the overall carbon footprint of the sneaker down to 12.4 kg of CO2.

But, these plastic bottles still have to go through the materials processing stage. They’re not going into the sneakers as plastic bottles. They need to be turned into the Primeknit material.

Recycled polyester takes approximately 84% less energy than it does to use virgin polyester.

So, 84% of the energy used to manufacture materials for the upper can be eliminated.

The carbon emissions in producing the materials to manufacture this part of the sneaker becomes 0.26 kg of CO2 compared to the original 1.6 kg.

Adding that back into the mix, the total carbon footprint is still at least 12.66 kg of CO2.

Overall, that’s a maximum reduction of around 9.6% or 1.33 kg of carbon emissions eliminated.

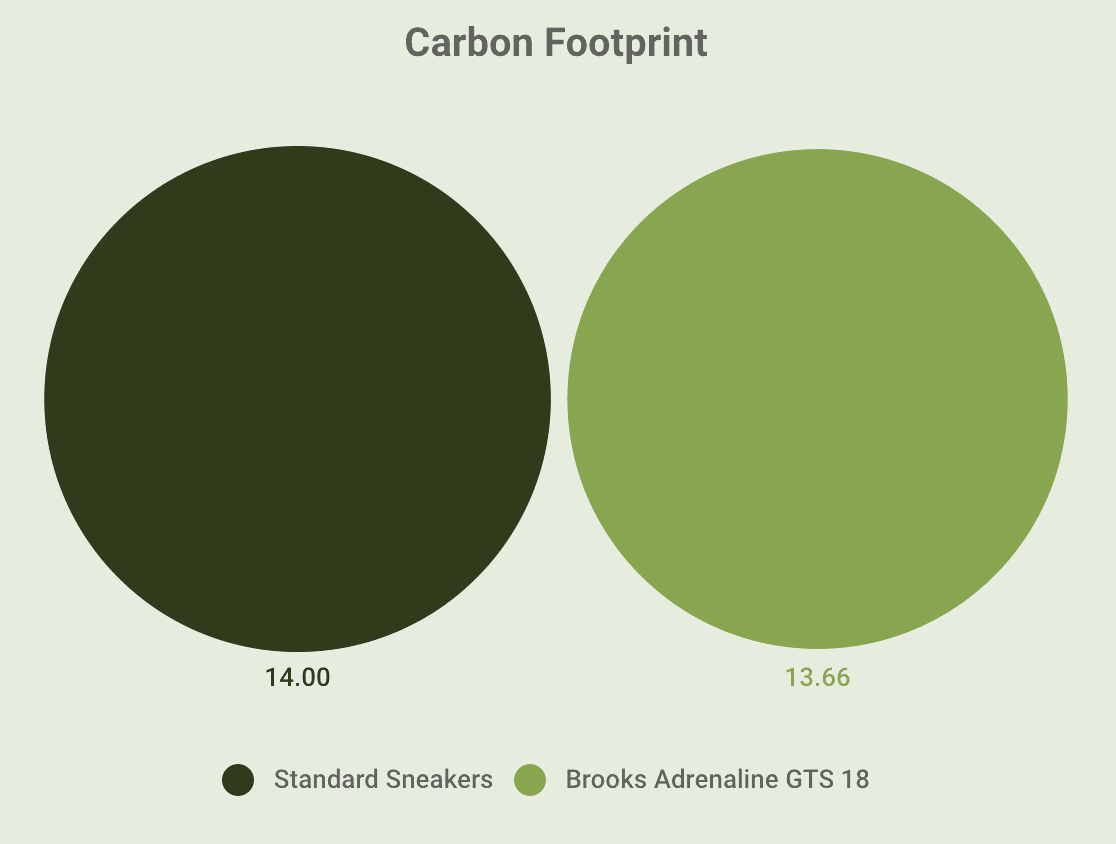

Brooks Adrenaline GTS 18

| Carbon Emissions | Reduction in Emissions | % of Reduction |

| 13.66 kg | 0.34 kg | 2.5% |

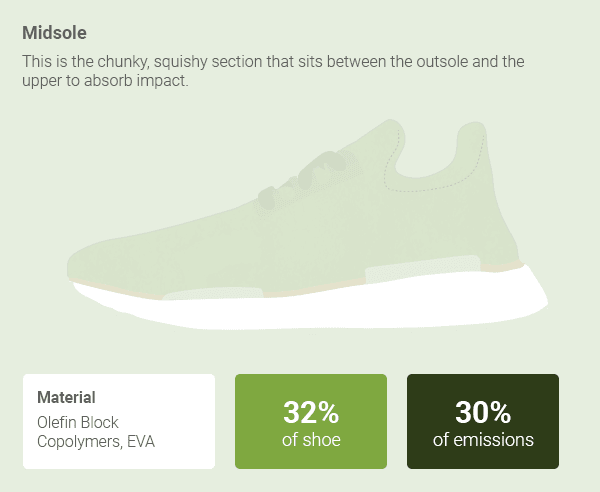

The Brooks Adrenaline range includes a biodegradable midsole.

Given that only 0.5kg of carbon emissions result from the end of life phase of the shoe, the maximum impact making the shoe biodegradable can have on the carbon footprint is a reduction of 0.5 kg.

However, that would be if 100% of the shoe is biodegradable.

Only the midsole is biodegradable. It makes up just under 1/3 of the shoes.

So, this environmentally friendly effort only managed to reduce the overall carbon footprint by 0.34 kg down to 13.66 kg.

That’s a saving of just under 2.5%.

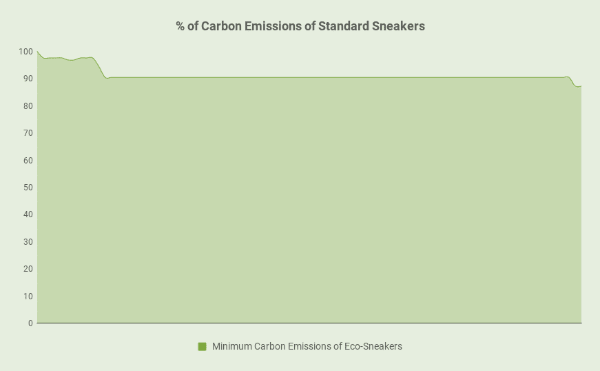

Summary of Environmental Impact of Eco Sneakers

| Avg. Carbon Emissions | Avg. Reduction in Emissions | Avg. % of Reduction |

| 12.72 kg | 1.28 kg | 9.12% |

The results from analyzing the 89 eco-sneakers in the RunRepeat database are that the maximum reduction in carbon emissions from any sneakers currently on the market is less than 13%.

By using the information available from the study, it is also possible to calculate the carbon emissions from a sneaker made from 100% recycled materials.

It would be 10.64 kg of carbon emissions.

That’s only a saving of 24% -- with 100% recycled materials.

This confirms the only way to make real, meaningful reductions in the carbon footprint of sneakers is to improve at the entire process from rainforest to landfill.

Buying fewer sneakers more effective than buying eco-sneakers

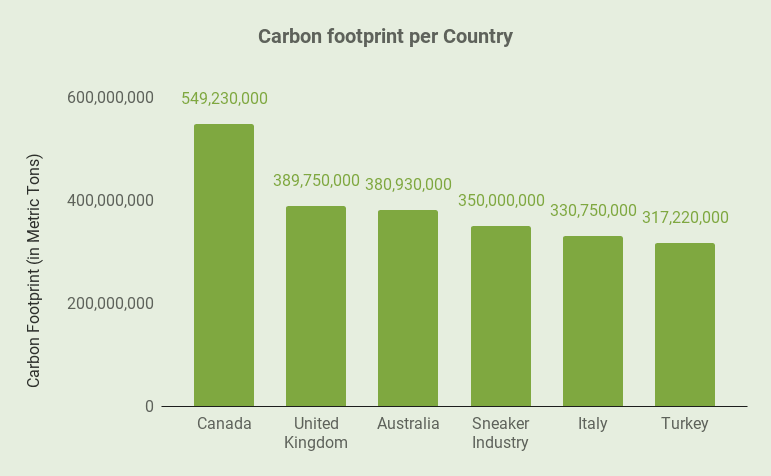

With an estimated 25 billion sneakers manufactured last year, it adds up to an estimated 350 million metric tons of CO2 emissions from the global sneakers industry.

That puts the sneaker industry in the same ballpark as Canada, the UK, Australia, Italy, and Turkey when it comes to carbon emissions.

In fact, if the sneaker industry was a country, It would be the world’s 17th largest polluter.

It’s a global issue, but as ever, the US is a major driver of the problem. The average American buys 7 pairs of shoes per year.

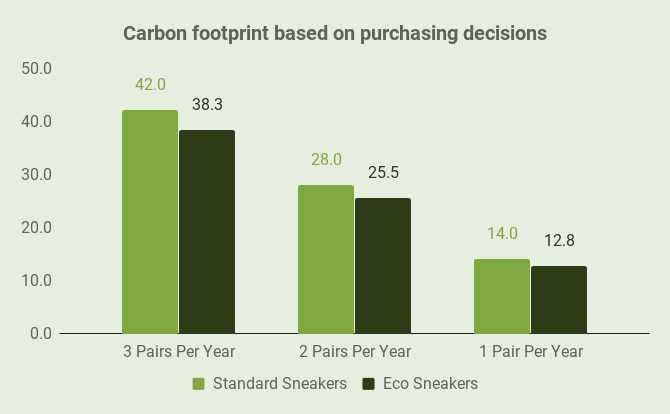

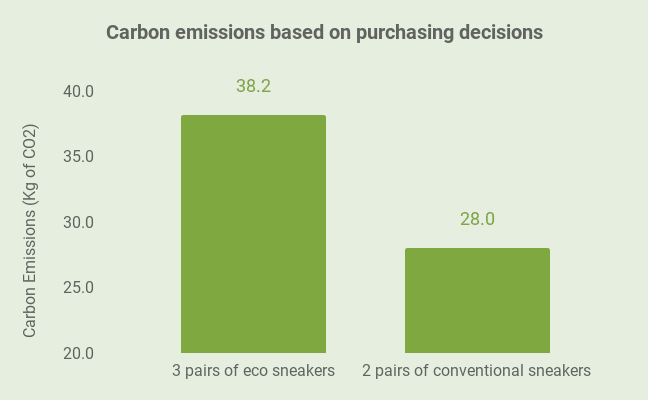

From those seven pairs, it’s estimated 3 pairs are athletic shoes -- that’s 42 kg of carbon emissions per year, per person in the USA.

The average pair of eco-sneakers equates to 12.77kg of carbon emissions.

If each person buys eco-sneakers, their carbon emissions fall to 38.31kg per year rather than 42 kg.

That’s a reduction of 8.8%.

However, purchasing eco-sneakers isn’t the most effective way to bring down that carbon footprint.

The most effective thing a consumer can do is to buy one less pair of sneakers per year -- cutting their carbon footprint by a third.

Buying fewer pairs of sneakers will always be more effective than buying eco sneakers.

If companies were really serious about saving the planet, they would make their sneakers more durable, release fewer variations, and work to change buying behavior from one of consumerism to one of practicality.

This is where things get difficult for the major athletic footwear brands. Nike is never going to tell customers to buy fewer pairs of sneakers.

Eco-sneakers are more expensive

The average pair of sneakers is listed at $111.00. The average pair of eco-sneakers is listed at $159.79.

Eco sneakers cost $48.79 more or a 69.4% markup.

Manufacturers feel comfortable charging an eco-premium or eco-tax of $48.79 for carbon emissions savings of 1.3 kg -- that’s a 69.4% markup.

With an average price increase of$48.79, and an average carbon emission saving of 1.33 kg - the average environmentally conscious consumer is being charged $37.59 for every kg of carbon emissions eliminated.

That seems a crazy amount of money. Especially when it is put into the context of carbon taxes.

Here is what various institutions have recommended for an appropriate carbon tax:

- UN IPPC: $135 - $5,500 per metric ton of emissions

- Obama Administration: $50 per metric ton of emissions

- Trump Administration: $7 per metric ton of emissions

- Eco Sneakers: $37,590 per metric ton of emissions saved

While governments are proposing placing carbon taxes on companies to deter from increasing their carbon footprint, sneaker companies are putting an eco-premium on their shoes.

What are Adidas and Nike doing about their environmental impact?

Sneaker companies have a duty to create value for their shareholders.

It’s difficult to have an objective to sell more sneakers and reduce your impact on the environment.

These two things are mutually exclusive.

To understand what companies are doing, it makes sense to look at the sustainability/ environmental targets of two of the largest players in the athletic footwear space:

Nike and Adidas.

They each have major environmental targets set for 2020:

| Nike | Adidas |

| Double business while halving environmental impact. |

To become a sustainable company by:

|

Nike’s goal is clear and concise -- they want to halve their environmental impact.

It can be assessed, measured and at the end of the day, you can see whether or not they’ve achieved it.

Adidas have left things a little more open to interpretation.

It all depends on their definition of sustainable.

If you take them at face value, their objective goes even further than Nike.

Nike

Main Objective: Double business while halving environmental impact.

Supplementary Targets:

| 100% renewable energy at owned and operated factories, offices and shops | 100% sustainable contract factories | Reduce Avg. Product Carbon Footprint by 10% |

| 100% of cotton sourced sustainably | Reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions per kg in textile dyeing and finishing by 35% | Decrease energy consumption and carbon emissions per unit by 25% - key operations |

| Zero waste to landfill by footwear manufacturing | Reduce Freshwater Use Per Kg – Textile Dyeing and Finishing by 20% | 100% of materials in compliance with Nike’s own Restricted Substance list and Nike’s Wastewater Quality Requirements |

Nike has an ambitious target to ‘double our business while halving their environmental impact.’

But what does this actually mean?

In practice, Nike’s aim is to halve the environmental impact per unit of product. A unit can be a t-shirt, a pair of sneakers or any product in their range.

But, if the aim is to double the size of their business in the same period, then surely this grand objective is simply to continue polluting at the same rate by 2020?

100% Renewable Energy

‘100% renewable energy at owned and operated factories, offices and shops’.

Nike’s target is to implement 100% renewable energy at owned and operated factories, offices and shops -- not at contract factories.

The impact that Nike owned and operated facilities have on the environment are not particularly significant.

It’s better to do it than not do it, but it’s not going to have the impact that would have been achievable by putting pressure on their contract factories to invest in renewable energy.

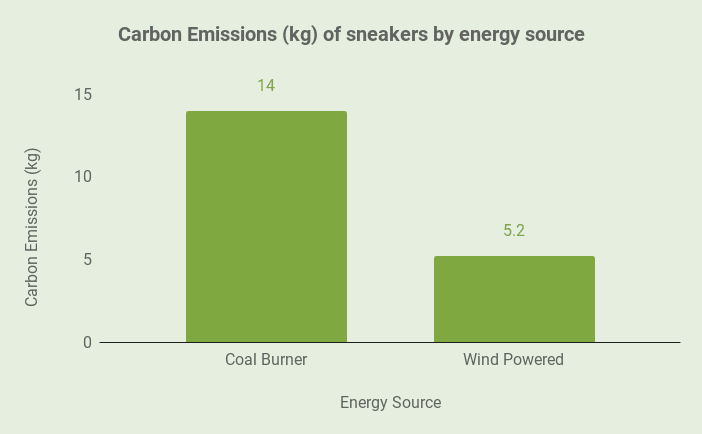

The majority of carbon emissions come from energy in the manufacturing process -- up to 64%.

So, it’s a prime area to target for carbon reduction.

How would that look in practice?

For example, emissions from offshore wind are approximately 1.5% of emissions from a coal burner. If Nike were to use 100% wind energy at their factories, they cut potentially the carbon footprint of a pair of sneakers by as much as 62.9% (8.8 kg) per pair.

Those savings would be incredible, but Nike are not putting pressure on their factories to make this possible.

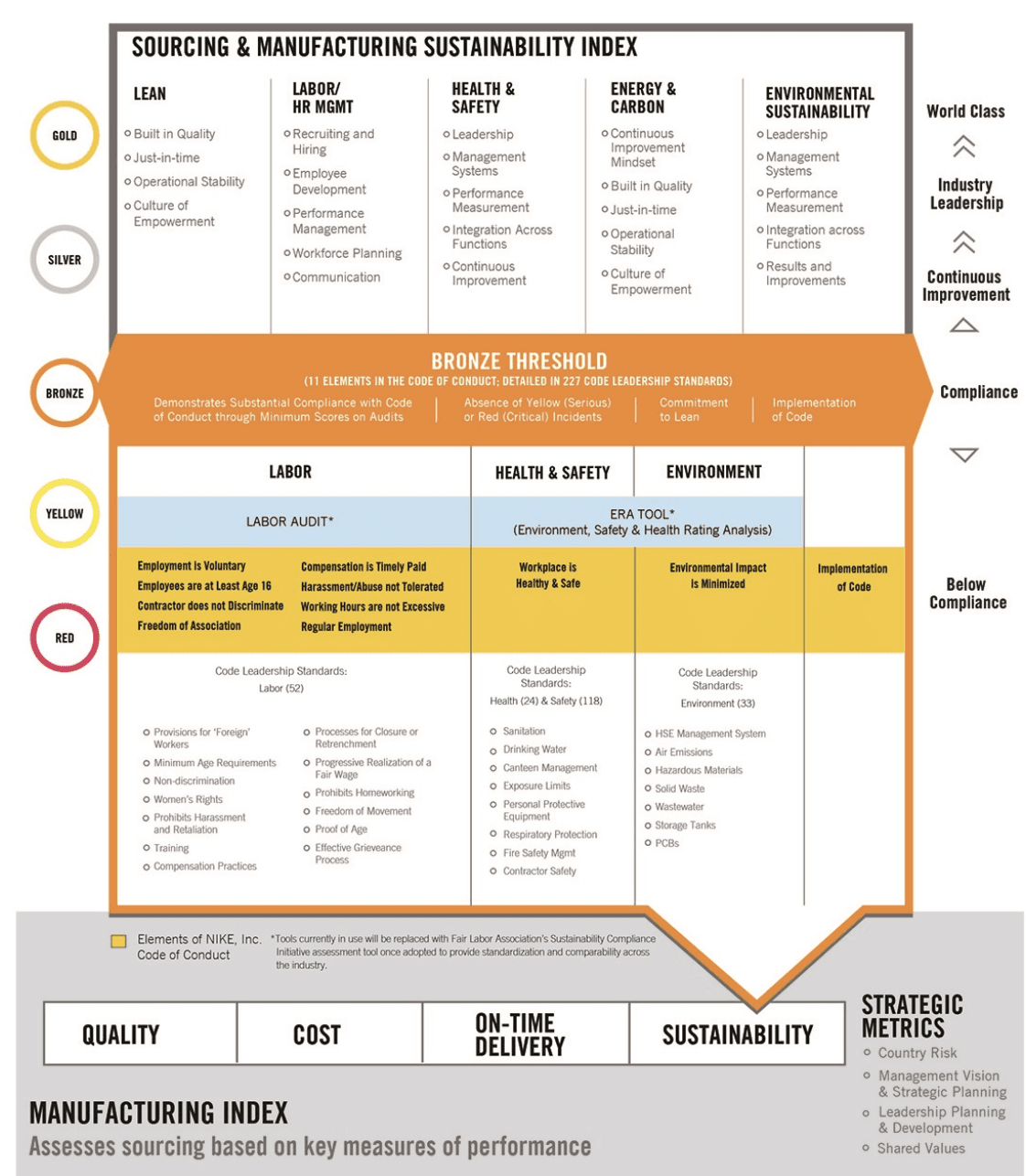

100% sustainable contract factories

There’s very little detail when it comes to the environmental aspects of Nike’s contract factories.

Definitions are very important in deciding whether targets are genuine, or just marketing talk.

The UN World Commission on Environment and Development describe sustainable production as production that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

It’s easy to play fast and loose with words, but they have to have a meaning in this context.

To be considered ‘sustainable’ it appears factories only need to reach bronze on Nike’s own certification scale.

Source: Nike Company Blog

It’s clear environmental impact is a factor, but it’s also clear that it is not the only factor. It’s maybe not even an important factor.

The use of sustainable here is inappropriate.

The level of carbon emissions in the footwear market is unsustainable and requires radical action.

This is simply a case of using sustainable as a buzzword.

It’s meaningless.

Reduce Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions

Reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions per kg in textile dyeing and finishing by 35% and Decrease energy consumption and carbon emissions per unit by 25% in Key Operations.

A reduction of 35% or 25% per unit while the number of units doubles is still a net increase in carbon emissions.

Reduce Avg. Product Carbon Footprint by 10%

If Nike is truly going to double their business on a per unit basis and only reduce their product carbon footprint by 10% -- it’s not good enough.

Zero Waste To Landfill By Footwear Manufacturing

Zero waste to landfill is a notable target.

If scrapped material can be reprocessed and turned to be used in sneakers it would be fantastic.

However, reducing the amount of scrap in the first place is still important. Although the energy requirements are significantly less to turn scrapped material back into usable material, it does still require energy.

If steps can be taken to reduce the amount of scrap material in the first place these dual objectives would be ideal.

Reduce Freshwater Use Per Kg – Textile Dyeing and Finishing by 20%

Water is a finite resource. So any reduction in freshwater usage is a positive step.

The key phrase, however, is ‘per kg.’

Reducing freshwater use by a fifth is excellent. But, if you are going to increase the volume of textiles needing to be dyed by more than 20%, then Nike is still increasing the net rate of pollution.

This is a recurring theme throughout the entire literature on their website.

There are reasons for this.

Firstly, a per unit basis is an easy way to measure - whether it is per kg, or per liter, or any other unit of measurement.

It is also an easy way for Nike to standardize their measurements across various business units - footwear, clothing, sporting equipment, etc.

On the other hand, it can help mislead. It’s easier to disguise than overall or total values. Nike uses the per unit measurements as a way to disguise the true scale of their pollution and the ineffectiveness of their targets.

Programs and Innovation

Nike has some areas of interest/ innovation in the sustainability field:

- Nike Grind

- Nike Colordry

- Nike Flyleather

- Nike Flyknit and Recycled Polyester

Nike Grind goes hand in hand with the Nike Reuse-a-Shoe program designed to reduce the impact of sneakers at the end of life stage.

Currently, more than 85% of shoes are sent to landfill or incinerated at the end of their usable life. The Nike Reuse-a-Shoe program provides an alternative for consumers.

They can donate their unwanted shoes to Nike who will grind up the shoes and turn them into running tracks, basketball courts, and gym floors.

Nike Colordry is a dyeing technique that dyes fabrics without the use of water. Nike dyes an estimated 39 million tonnes of polyester each year. It’s also estimated that each kilogram of that polyester requires 100-150 liters of water to dye.

Nike Colordry replaces all of this water, reduces energy consumption in the process whilst eliminating the use of some chemicals traditionally used in the dying process.

It is innovations like this that will have a significant impact in the fight against climate change, and give Nike the chance of becoming a sustainable organization.

Flyleather is made from the scrap pieces cut off conventional leather. It’s combined with synthetic materials to produce a high-performance leather replica. This has significantly lower carbon emissions than conventional leather, but, that does not mean it is friendlier than other materials out there.

Flyknit is a material partly made from recycled plastic bottles diverted from landfill. Without going into the performance benefits of Flyknit, it is a material that has a lower carbon footprint because it is using recycled materials.

Overall, you can tell Nike clearly are putting time and effort into the research and development necessary to achieve their goals, even if the way they present their objectives does leave a bad taste in the mouth.

Adidas

Main Objective: To become a sustainable business.

Supplementary Targets:

| 20% water savings at strategic suppliers | 35% water savings at apparel material suppliers | 35% water savings per employee at own sites |

| 20% waste reduction at strategic suppliers | 50% waste diversion for owned operations to minimize landfill | 75% paper reduction per employee at our own sites |

| Achieve 100% sustainable cotton | Reduce use of virgin plastic (use only recycled plastic by 2024) | Increase design and use of sustainable materials in stores |

| Rolling out a global product take-back program to all our key cities and markets | Investing in materials, processes and innovative machinery which will allow us to upcycle materials into products and reduce waste. Ongoing examples include Sports Infinity and Futurecraft Tailored Fibre |

Achieving 100% sustainable input chemistry by adopting the ZDHC MRSL 8 and Bluesign Bluefinder |

Adidas use the phrase ‘sustainable’.

The problem is that ‘sustainable’ means so many different things to different people.

For the sake of this article, I’m using by the UN WCED definition:

“meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

This means using sustainable energy, using water in a sustainable way, and using chemicals that do not pollute the ground and groundwater surrounding factories in poor or vulnerable countries.

However, Adidas define being sustainable as follows:

“Being a sustainable business is about striking the balance between shareholder expectations and the needs and concerns of our employees and consumers, the workers in our supply chain and the environment.”

This is a very different definition of sustainable than the UN WCED definition. In fact, it’s meaningless and cannot be measured.

Water Savings

Adidas have water savings targets of:

- 20% water savings at strategic suppliers

- 35% water savings at apparel material suppliers

- 35% water savings per employee at own sites

To keep costs low, Adidas outsource almost 100% of their manufacturing to factories around the world. These are referred to as ‘strategic suppliers.’

‘Apparel material suppliers’ are defined as ‘specialists in printing and dyeing operations.’

‘Own sites’ are defined as ‘including administrative offices, production facilities, and distribution centers.’

This target is very similar to the Nike target and the same logic applies.

It’s great to reduce water usage, but it depends whether they are reducing total water usage or reducing water usage per unit.

An overall increase in water usage being marketed as a decrease is disingenuous.

Waste Reduction

Adidas have the following waste reduction targets:

- 20% waste reduction at strategic suppliers

- 50% waste diversion for owned operations to minimize landfill

- 75% paper reduction per employee at our own sites

In the context of the overall emissions of Adidas, the paper per employee at their own sites barely touches the sides.

Similarly, 50% waste diversion for owned operations to minimize landfill is a disappointing target given Adidas say in their annual report that they “outsource almost 100% of production to independent third-party suppliers.”

In effect, this is a false target -- it’s meaningless.

The 20% waste reduction target is the only target out of these three that isn’t conceived to deceive.

There, 20% just is not sufficient.

In general, Adidas is not using their clout as a major player in the industry to put pressure on suppliers to comply with certain standards.

Although Nike’s standards are not perfect, they at least have a clear, strong baseline with facilities in place to terminate contracts if contract factories are not meeting specific standards.

Nike uses its position in the marketplace to coerce these suppliers into complying or they will lose business.

For the sake of the environment, Adidas needs to step up and do the same.

Use of Materials

- Achieve 100% sustainable cotton

- Reduce use of virgin plastic (use only recycled plastic by 2024)

- Increase design and use of sustainable materials in stores

Sustainable cotton is a troubling example. One where the word ‘sustainable’ really matters.

Cotton has a huge environmental impact when it comes to:

- Water usage

- Land usage

- Use of pesticides and insecticides

To produce one kilogram of cotton (about the equivalent of a t-shirt and a pair of jeans) it can take more than 20,000 liters of water.

Cotton also takes a lot of land to grow. This leads to an increase in deforestation.

At the same time, cotton uses more pesticides and insecticides than any other crop in the world.

Organic cotton doesn’t use insecticides or pesticides. But, because conventional cotton plants have a higher yield than organic cotton plants, it actually takes even more land and water to grow organic cotton.

Where conventional cotton uses 290 gallons of water to produce a t-shirt, organic cotton requires 660 gallons.

That’s where definitions become important.

Nike defines sustainable cotton as “cotton that is either certified organic, BCI Better Cotton, or is recycled.”

Adidas isn’t as specific but talks about reducing the use of pesticides, promoting efficient water use and crop rotation.

One outcome of achieving their 2020 targets may be using significantly more water than they would have by using conventional methods.

It’s difficult to make a decision on whether these companies are acting in bad faith, are exaggerating their green credentials or are actually making a genuine attempt to make a difference.

Improve End of Life Options

This is where Adidas is miles behind Nike.

Nike has the reuse a shoe program that’s intertwined with Nike Grind -- there’s a process there.

Adidas don’t have that yet.

For a single pair of sneakers, the end of life stage is not a massive contributor to pollution. But, when you consider 25 millions pairs of sneakers are being manufactured each year, and 85% of sneakers are sent to landfill or incineration, it starts to become an issue.

If shoes can be designed to be recycled into more sneakers, it can make a difference. With 100% recycled materials, emissions can be cut by 24%. From there, companies can start to focus on manufacturing processes to reduce the remaining emissions.

Summary of Company Environmental Targets

Based on the analysis:

- Adidas don’t currently have the infrastructure in place to become a sustainable company.

- If Nike achieves its targets, it will still be polluting at at least the same rate they are now.

These are the two companies with the largest budgets, the greatest leverage over suppliers and the most resources to throw at the issue.

At the moment, they’re not doing enough to make a serious difference. There are options to significantly reduce their environmental impact -- starting with cleaner energy.

Overall, it seems as though both companies are dipping their toes in the water, but they don’t want to get wet.

Conclusion

The sneaker industry is a microcosm of the issues the world faces in fighting climate change.

Nike and Adidas don’t really care that much about the environment. They just want you to think they do so that you’ll buy more sneakers.

Sneakers that they tell you will save the planet when, in fact, they’ll do the exact opposite -- just perhaps at a slightly slower rate.

Oh yeah, and they’ll charge you an extra $48.79 for the pleasure.

If you want to save the planet, don’t buy eco-sneakers. Try just buying fewer pairs.

Methodology

The vast majority of carbon emissions information is based an MIT study titled ‘Manufacturing-focused Emissions Reductions In Footwear Production’ by Cheah et al. 2013.

In this paper, Cheah defines the carbon emissions (kg of CO2 equivalent gases) for different stages of the lifecycle of a pair of sneakers, and for each material within the sneaker.

With this information, we were able to understand the makeup of each section of the sneakers and its contribution to the CO2 emissions.

When looking at the eco-sneakers, we were able to understand the eco-element of the sneaker, - be it a recycled upper or biodegradable midsole - understand what proportion of the emissions it was responsible for, and replace the emissions with those expected from the replacement material or process.

Definitions

Sustainable - Meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Renewable - Not depleted when used. Capable of being regenerated.

Carbon Emissions - The release of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. Calculated as carbon dioxide equivalents.

Eco-Friendly Sneakers (Eco Sneaker) - At least one element of the shoe or a material the shoe is made from is advertised by the manufacturer as green, biodegradable, sustainable, eco-friendly, or environmentally friendly or any variation or synonym of these terms.

Access to data, about Danny and RunRepeat

All data is publicly available in this spreadsheet. If you want more detailed data, reach out. Prices include all 1749 running shoes and 2275 sneakers at RunRepeat. For any questions about the data or this article, contact Danny at danny@runrepeat.com.

Danny is a sneaker expert at RunRepeat who is conscious of the impact that mass consumerism and the sneaker industry as a whole is having on the environment. Regardless, he still loves sneakers, but will not be buying a new pair until he wears his current collection out.