Was Doping Worth it? Russian Athletics Decline [24K Results Analysed]

This is a follow-up piece on our previous in-depth research on doping and performance of Russian athletes.

We analysed 24,020 track and field results from 3,731 events and 400 Russian athletes to understand the consequences of doping.

The 400 athletes competed at the Olympic Games at least once during the 1993-2019 period. ANA (authorised neutral athletes) who qualified for the Olympic Games 2016, but did not compete due to the blanket ban, were included as well.

Key findings

According to our findings, despite systematic doping, the performance of Russian athletes is getting worse.

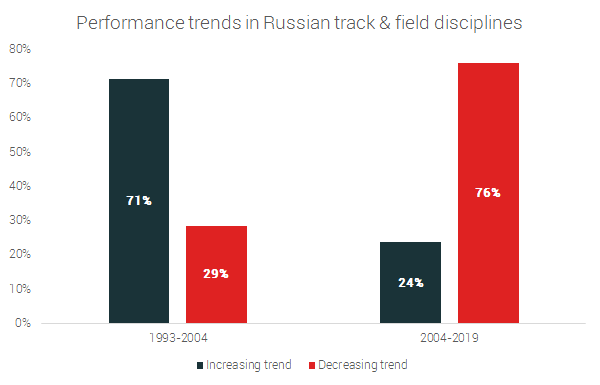

- Since 2004, 76% of disciplines have observed a decreasing trend in best yearly performance.

- Only 5.6% of all athletes had their PB disqualified for doping

We examined two factors:

- The season-best performances for all disciplines over this time period

- The percentage of athletes that achieved their Personal Best (PB) during the disqualification period

Season-best performance analysis

We analysed the season-best results during the 1993-2019 period in 42 disciplines (21 male and 21 female) to understand the trends in performance - are Russians getting better or worse?

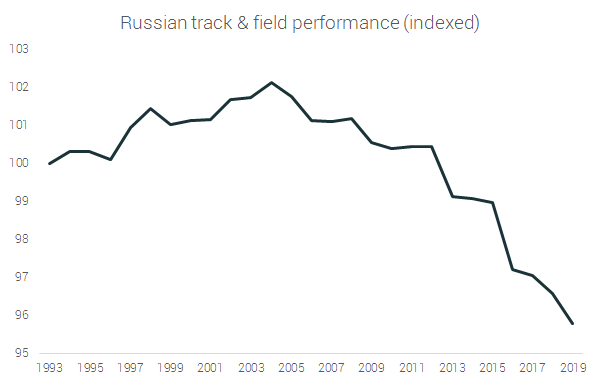

To get an idea of how Russian athletes performed as a whole, we grouped all disciplines (represented by season-best results) into an index from 1993 to 2019. This reflects athletes’ average performance over time compared to how they did in 1993.

In 2004, there was a turning point where the performance began to decline in 76% of disciplines. Before this, 71% of disciplines were seeing an improvement.

Personal-best analysis: % of disqualified results

Due to retroactive testing and disqualifications, athletes have competed but their results have been retroactively disqualified for doping at some point.

Results achieved during those periods are considered disqualified. All other results are considered regular.

In the 1993-2019 period, only 5.6% of all athletes had their PB disqualified for doping. This means they have achieved those results during the disqualification period. This number is surprisingly low given the number of disqualifications for doping.

As we’ve shown in our previous research, women had a 2x greater share of disqualified athletes than men. Now, looking at personal bests, 6.7% of women and 3.7% of men had their PB disqualified for doping.

If we look only at athletes banned for doping, only 23.9% of them had their PB disqualified for doping.

Note: Athletes who have competed in more than one discipline have been taken into account and considered as a unique athlete-discipline combination.

Conclusion

Both findings were unexpected. We expected to see season-best performance progress in the majority of disciplines, due to systematic doping and retroactive testing, and we expected to see a greater number of disqualified personal bests.