Running Cadence: What It Is, Why It Matters and How To Improve It

Don’t trust the 180-cadence belief. Optimal cadence for you is a range, not a single number you need to hit. Even if you hit it, it will still be influenced by terrain, your biomechanics, speed.

Increasing the cadence can lead to huge improvements. At the same time, you can work on other aspects of running and fitness level to make the best of it. This guide covers it all.

What is running cadence

A cadence is a number that says how many times your both feet touch the ground in a minute.

It can be calculated as the number of strides per minute (counting how many times one foot hits the ground) multiplied by 2, so you get the number of steps per minute.

If expressed in strides per minute (strides min-1), it describes the duration of a complete stride cycle (left and right step). Otherwise, steps per minute describe an actual number of steps made by both legs.

Why cadence matters

Cadence has a great impact on running and runners. It can:

- Help improve running efficiency,

- Reduce overstriding and enhance running form,

- Decrease impact forces on feet, ankles, knees,

- Reduce injury rates.

While it should not be the only focus if you’re working on your running form, it actually has the potential to transform your running.

How can increased cadence change your running

Here’s a scientific overview of the possible effects cadence can have on you and your running form:

| Running cadence: a scientific overview | |

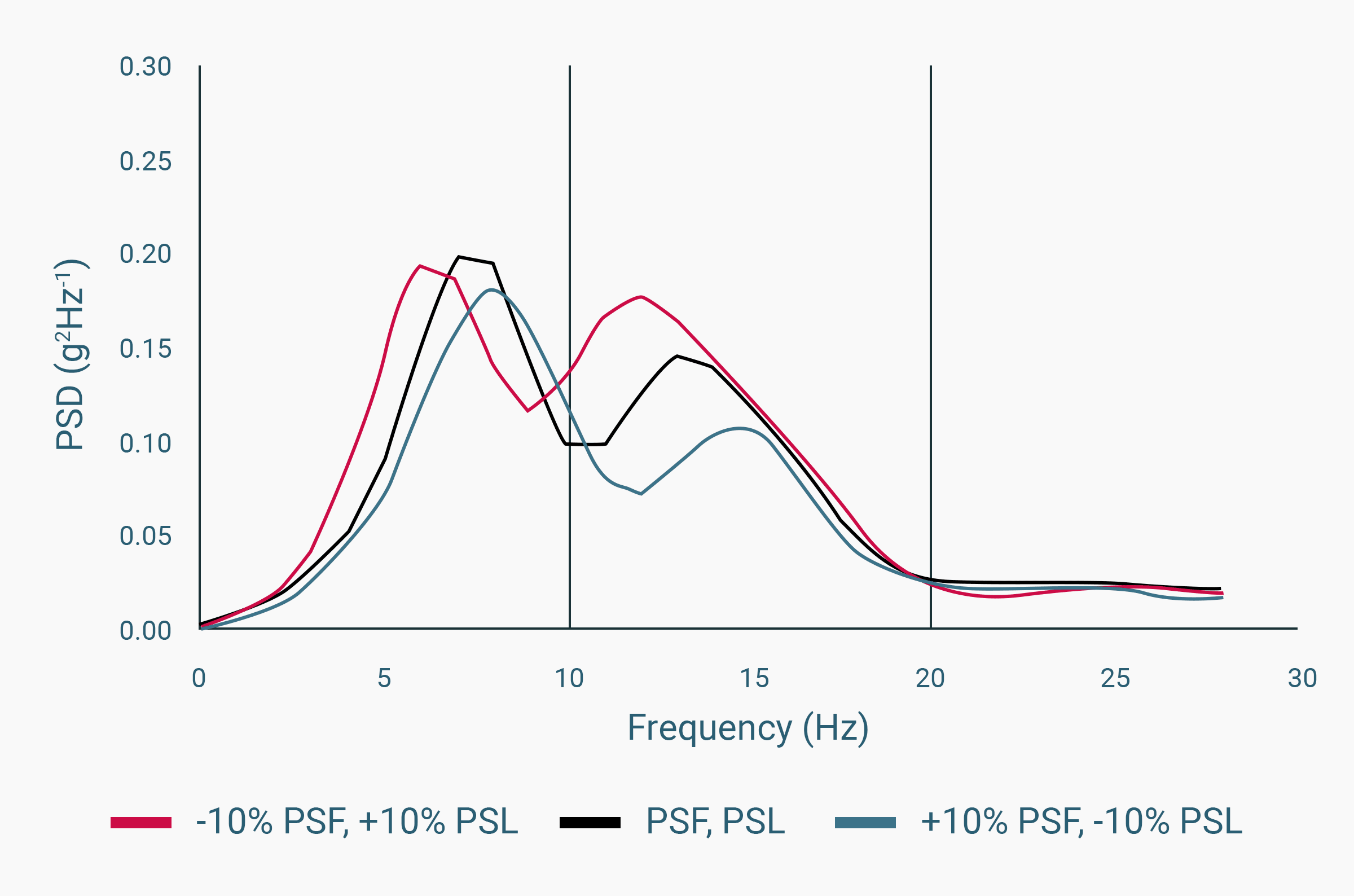

| Injuries and impact forces | Increased cadence means weaker impact forces. (With weaker forces come fewer injuries.) |

Same speed, 3 different cases: preferred stride frequency (84), 10% smaller (76), and 10% higher stride frequency (93). Faster cadence shows a reduced impact force. Source. |

|

| Overstriding | Increasing the cadence resulted in a reduction in overstriding (as shown here and here). |

| Shock attenuation | When increasing the stride length (decreasing cadence), shock attenuation increases as well and knees joints absorb the most of it. Read more about this here. |

| Barefoot running | Barefoot running tends to have a higher cadence than shod running (read more). |

| Leg stiffness | Leg spring should become stiffer in order to get to higher stride frequencies. (Leg spring is the body’s complex system of muscle, tendon and ligament springs that together act as a single linear spring.) Read more about this here. |

| Injuries | Increasing the cadence may reduce the risk of impact-related running injuries (source). |

| Increasing cadence may help with overuse injuries associated with elevated plantar loading (as shown here). | |

| Increasing the cadence may prove beneficial in the prevention and treatment of common running-related injuries due to a substantial reduction in the loading to the hip and knee joints during running (source). | |

| According to this metareview (10 studies), increased stride rate reduces many biomechanical factors associated with running injuries. | |

| Running economy | Training to run at a faster cadence may be a viable technique to improve your running economy (study). |

| Oxygen uptake | Inexperienced runners are equally capable of optimising stride length for minimal oxygen uptake as experienced runners (read more here). |

Optimal cadence: myth-busting and recommendations

There’s a widespread belief that 180 steps/minute is the cadence to aim for. Here’s a short background of how it happened:

- It was highly promoted in Daniel’s Running Formula book. Recommended as a great read, BUT the 180 cadence was based on elite runners only. And cadence changes with speed. Even elite runners have a slower cadence when jogging and not racing (source).

- Another book, Born to run, suggested that higher cadence is better especially for technical (trail) terrain.

- A study of 20 runners at the 100K World Championships found that their average cadence was 182 steps/minute. The average should be bold here. The variation in cadence between runners was significant: from 155 for one runner to 203 for another runner.

- Studies have shown that the optimal cadence is 180 (source), 170 (study) and 166 (source).

What’s the actual optimal cadence? Depends on the speed of your easy runs (among other things). Check the cadence during your easy runs:

- If your easy run pace is <10min/mile (6min/km), your cadence might be closer to 160, rather than 180.

- If your easy run pace is >10min/mile (6min/km), your cadence might be closer to 170.

These numbers serve to give context. Keep in mind all the factors that might and will affect your cadence (covered in the next chapter).

What this all goes to prove is that:

- There’s no universal and ideal cadence for running. Not everyone can nor should aim for the same stride rate. The top 25 runners at the above-mentioned 100k World Championships had a cadence ranging from 155 to 203.

- More experienced runners tend to have a higher cadence because they usually run faster than beginners.

- An average recreational runner has no obligation to reproduce the cadence of Olympic runners.

- It’s not about you only - there are multiple factors that have an impact on the cadence. Keep reading to learn more.

Factors that influence cadence

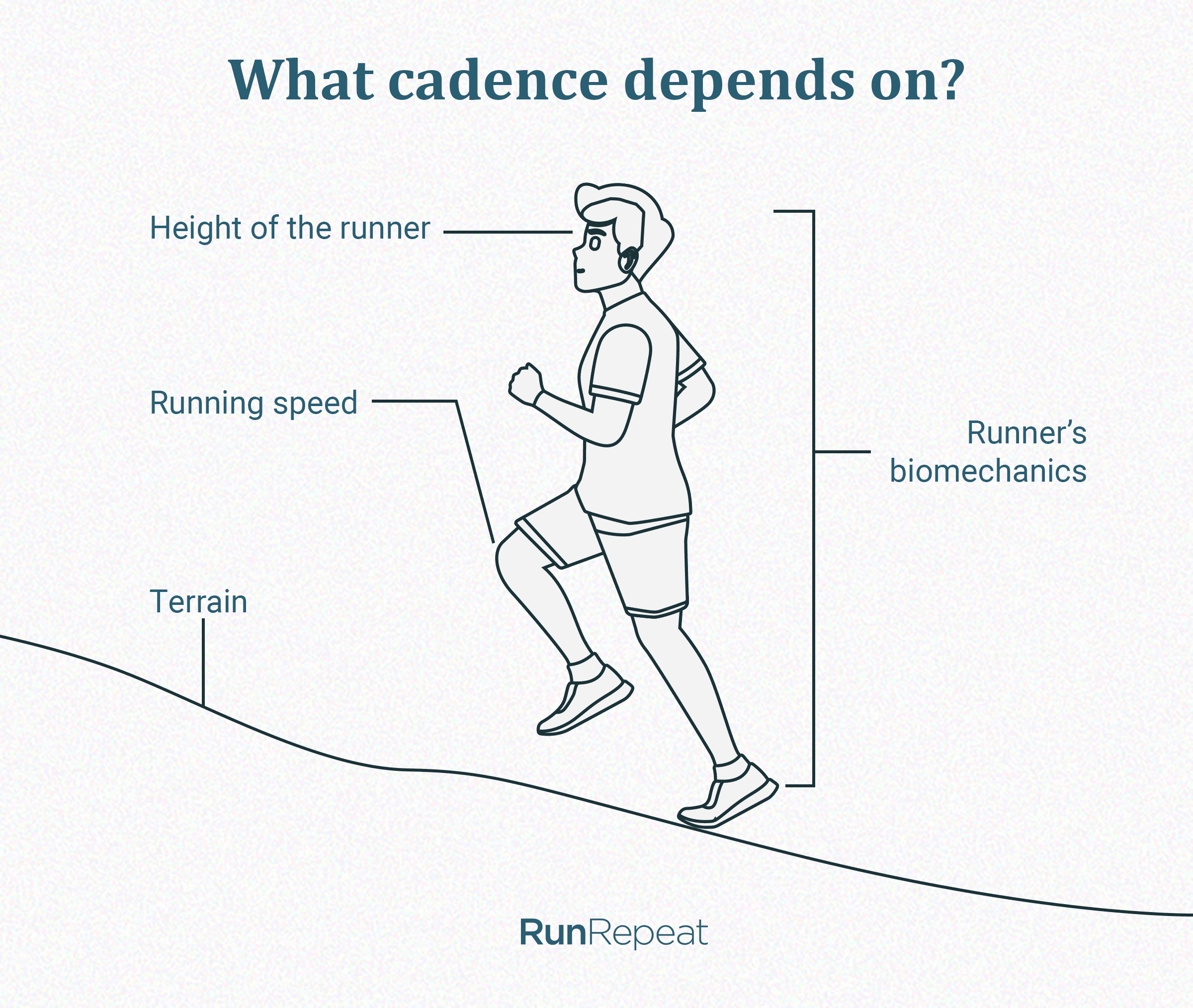

Cadence can vary dramatically. It’s not a standalone thing, but a piece of the puzzle. This chapter explains why it’s impossible to stick to the constant cadence no matter what.

Cadence depends on:

- Terrain. At steep uphills/downhills chances are you won’t be able to stick to your preferred cadence no matter what. Think obstacles, mud, sliding due to bad traction and grip, etc.

- Height of the runner. Taller runners tend to have lower cadence. Their steps (stride lengths) are longer naturally.

- Runner’s biomechanics.

- Speed. Jogging or doing a recovery run might get you to 160 steps/minute. Sprinting can get you to 220 steps/minute. General advice is to focus on cadence when you’re running comfortably. Not doing fartleks or tempo runs.

Key takeaway: a cadence is a number that varies. Don’t focus on one number, but rather on an appropriate cadence range.

How to measure cadence

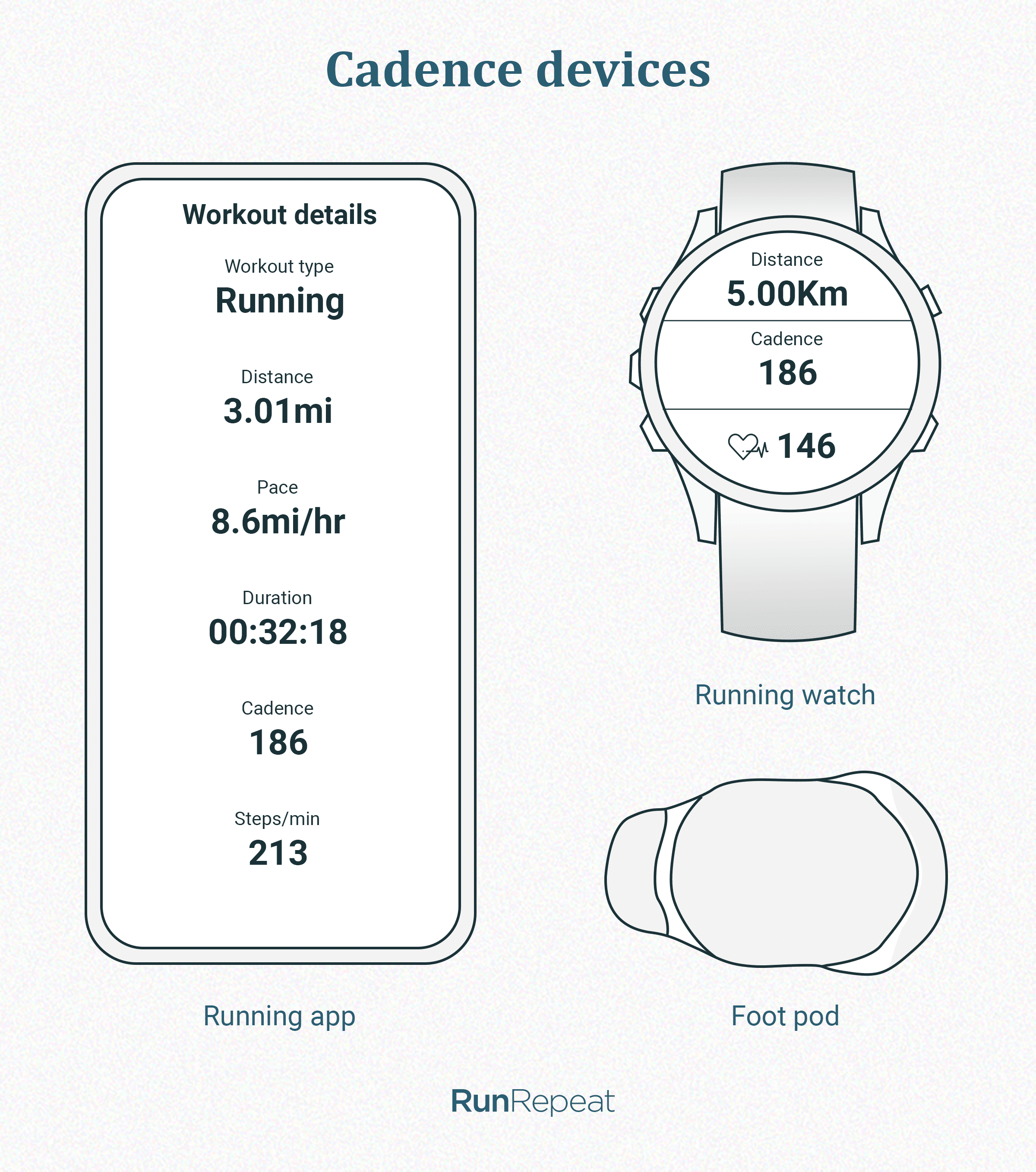

- Count it yourself. Count how many steps you make in 1 minute. If you count the steps of only one leg, you’ll need to multiply it by 2 to get the cadence.

- Use a running watch. Some watches have a built-in function for this.

- Use a foot pod. It’s a tiny device attached to your shoe that syncs with your phone or your watch. Make sure to always attach it to the same place on the shoe and to do it tightly. Also, you might need to calibrate it (unless using a Styrd).

How to change your cadence

First, figure out which cadence you’re aiming for. 180 steps/minute is not a golden rule. You can always start experimenting with it by increasing your cadence by 5%. Give it a few weeks and see what happens. Chances are, you’re in for a running treat (improvements across the board).

Once you decide on the goal, these things might help:

- Metronome (the device or an app),

- Music (Spotify and Youtube might help with this, there are lists of songs with given cadences. Then it’s up to you to adjust to the rhythm). Music tempo can even spontaneously impact running cadence. This effect is stronger for women than men (source);

- Running watch or an app that signals when you miss the set cadence (with or without a foot pod).

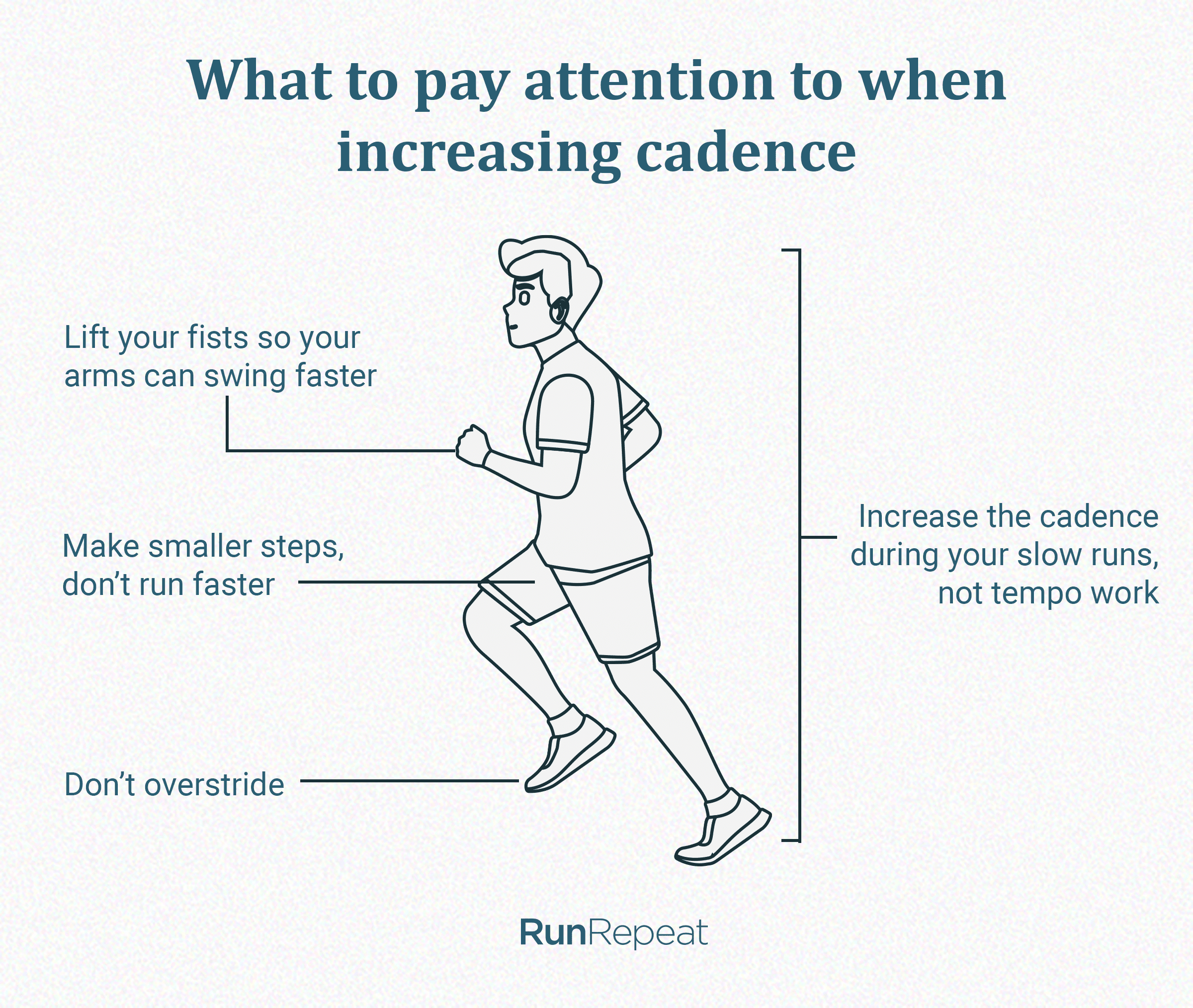

Along the way, make sure you:

- Try making smaller steps, not running faster. The majority of runners make this mistake and simply start running faster. If you’re struggling with keeping the same speed while increasing the cadence, try it on the treadmill. Set your preferred pace and then increase your step rate. Exercising this on a treadmill can do wonders for cadence increase. Chances are that the treadmill and the foot pod will give you different data. Trust your foot pod, not the treadmill.

- Focus on the cadence during your easy runs, not sprints.

- Pay attention to your arm position. Keeping your fists higher will help your arms swing faster.

- Stop overstriding. Overstriding usually leads to harsh heel strikes which slows you down and sends an extra shock to your muscles and bones. Check the heel-to-toe drop in your shoes. Heel drop might actually help with overstriding. Learn more about it in our in-depth guide on heel drop.

As mentioned above, try hitting these cadences according to your easy-run pace:

- 160+ if your easy pace is slower than 10min/mile (6min/km), or

- 170+ if your easy pace is faster than 10min/mile (6min/km).

If you’re a beginner runner, there are other activities that will help immensely in the cadence-improvement game. Your training should be structured and effective. Consider these:

- Do speed work. Intervals, sprints, fartleks. Regularly.

- Increase your mileage gradually by doing LSDs (long slow distance runs).

- Get stronger. Add strength training sessions.

- Give mobility exercises a try.

- If you’re a road runner, add trail running to your training schedule.

What to expect once you start increasing your cadence

You’ve been warned:

- It might feel funny. Weird. Like someone laced your shoes together. It’s all normal. It’s better to feel like this than to overstride (make too long strides).

- Heart rate increase. It might take a few weeks or months for your body and heart to adjust to the new cadence.

- Higher the cadence, the shorter the stride length. This means your calves will work more. If you feel that a bit too much, focus on exercises that will help ease the transition (e.g. stretching).

- You will need time to adapt.

Adaptation period

It might last a few weeks or a month to get used to the new cadence.

This study has shown that a 6-week program can increase the preferred running cadence by 5-10% in runners with a stride rate <85.

Data overload: what now?

If you’re a nerd and really into data on running, we recommend reading The Secret of Running: Maximum Performance Gains Through Effective Power Metering and Training Analysis. Even if you get a foot pod and a GPS running watch and the best shoes on the market, you still have the risk of having it all and not doing anything with it.

Data is only good if you know how to read it and make the best of it so it supports you on your way to becoming a better runner.